A blog about journalism and transparency

Note to readers: In 2023, I moved my blog to substack. You can access it and subscribe here.

Whoever pays the piper …

The House of Commons ETHI committee (aka the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics) kicked off yet another ‘study’ of the Access to Information Act on Oct. 5 with a 90-minute appearance by Caroline Maynard, Canada’s information commissioner.

Maynard was competent, insightful and well-spoken. Most of the MPs were not. Few of them understand the law. So these sessions often devolve into an Introduction to Access 101 – that is, whenever the partisan sniping subsides.

Maynard again cited her office’s crushing workload under an avalanche of complaints. No surprise there. Requestors now get the worst service since the law came into force in 1983. Few of her observations at committee were new, though the scale of system breakdown is unprecedented. Departments love to blame COVID, but all of the dismal trends she mentioned pre-date the pandemic.

Maynard did say something unexpected. Asked whether her office operated independently from government, she assured it did – with an important exception.

“The only part that is not clean, in my view, is the funding,” she said. “We have not been able to obtain an independent process under which we can get appropriate funding.”

Maynard’s annual budget is set by government, through the Treasury Board of Canada and ultimately by Finance Canada. She answers to Parliament for her work, as an officer of Parliament. But to pay for her work, she must go cap-in-hand to government ministers, whose departments she investigates on a daily basis.

At least two other officers of Parliament are funded independently of government. The Chief Electoral Officer and the Ethics Commissioner receive appropriations directly from Parliament. (Not so the Auditor General, remarkably.)

Maynard and her predecessor, Suzanne Legault, have been precariously funded for years, surviving on supplementary grants that disappear each year and have to be applied for again and again. There’s been some stability in recent budgets. But with caseloads rising each year, the office is always playing catch-up.

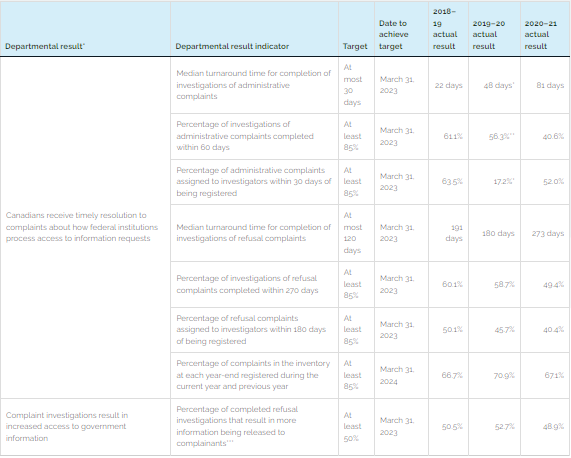

The information commissioner has 135 employees and spends $16 million annually to keep government honest. Performance targets are regularly missed, largely because of cash shortfalls. For example, average turnaround time for complaints about excessive blacking-out is targeted at 120 days. In 2020-21, the last year for which stats were posted, the average hit 273 days.

Treasury Board of Canada has been conducting a legislated review of the Act since June 2020. Results were promised in January 2022, but failed to appear. Now a report may come by the end of the year.

Submissions from the public have called for an array of reforms. But to my knowledge no one is calling for an independent funding mechanism for Maynard’s office. And that particular reform is clearly needed to prevent governments from quietly crippling the office’s effectiveness in holding them to account.

Oct. 9, 2022