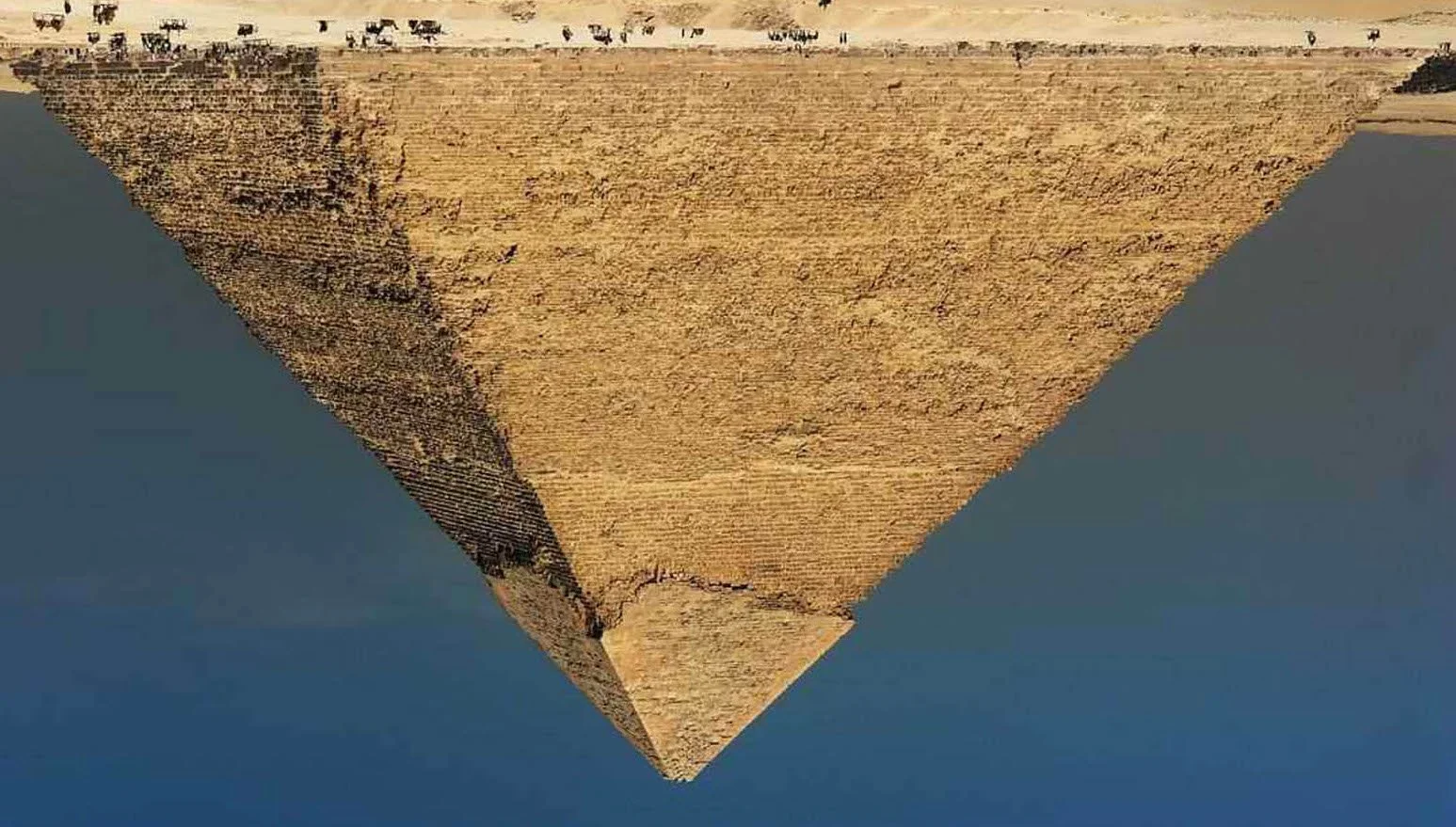

Upside-down tyranny

The ancients invented the pyramid, but journalists flipped it upside down. The so-called ‘inverted pyramid’ style of reportage, where the kernel of a news story sits at the top and secondary matter peters out toward the bottom, has been around for maybe 150 years. Historians differ about whether the form was germinated by the telegraph, the U.S. Civil War, the Lincoln assassination, the Associated Press (AP) wire service or all of the above. But it has stood the test of time, to the chagrin of some self-regarding reporters.

Upside-down prose is unnatural. No storyteller in ages past would ruin a tale by immediately giving away the ending. Everybody knows stories have a beginning, middle and end. Even if those bits get mixed up a little, you’ll lose your dramatic flow – and your audience – by starting out with a spoiler. Gravity-defying pyramids have no place even in casual conversation.

But they did solve technical problems in the news business. Telegraph lines were vulnerable to weather-related breaks and even sabotage. Tapping out the gist of a news story at the outset at least delivered the essentials before the line got cut. (Some historians discount this view.) Telegraph transmissions were costly, incentivizing a cut-to-the-chase style. AP also distributed copy to hundreds of different newspapers that might print one paragraph or all of them. Inverted pyramid stories are easily size-customized – just cut from the bottom up. The style also helped focus the mind of frazzled reporters, forcing them to decide what is core and what is dross.

The form also solved a very human problem, that is, the short attention span. Busy citizens may want just the steak, declining hors d’oeuvres, potatoes and apple pie. Some purists regard inverted pyramids as a literary abomination, but the structure is paradoxically reader friendly. Discriminating consumers can chose their own news adventure, whether a first-paragraph hop, a trip to the end of the line or some place in between.

Broadcasters catch a break from this upside-down tyranny. Radio and TV segments more often rely on traditional storytelling, with a narrative that flows from start to conclusion. Segments depend on listeners or viewers sticking around to the end, with a narrator’s voice ushering everyone forward.

Telegraph lines have long disappeared, replaced by ultra-capacity fibre optics that are reliable and cheap. The web’s elastic news holes have supplanted the rigid Tetris of newspaper columns. The emergence of broadcasting has nurtured an alternative format. Yet the style persists. “The inverted pyramid remains the Dracula of journalism,” said AP’s Bruce DeSilva. “It keeps rising from its coffin and sneaking into the paper.”

Long-form reportage, Q-and-As, new journalism, personal narratives, fact boxes, and other modes all have their place in post-modern news. But that quaint invention of the 19th century will be with us for many years yet. The technical hurdles it surmounted have passed into history, but the human ones have not. Busy people still want reporters to get straight to the point.

Feb. 1, 2022