The cost of transparency

Beware the politician who complains about the costs of responding to freedom-of-information requests. It’s almost always a ploy to kill transparency.

Take a recent example from British Columbia, where the NDP government dropped a bombshell bill last October to increase secrecy and charge a stiff fee for anyone with the temerity to file FOI requests.

Lisa Beare, Citizens’ Services minister, initially proposed a $25 fee for each request, up from zero. (It was later cut to $10 after an outcry.) In defending the move, she vilified frequent filers, such as the B.C. Liberal opposition, which she estimated cost the treasury $14.3 million for the 4,772 requests it made in 2020-21. Never mind that the NDP was also a frequent filer while in opposition.

The episode is a reminder that FOI does have a price tag, but any fair accounting would balance those costs with the savings that sunshine laws generate. FOI exposes fraud and waste and, just as important, discourages bad behavior today for fear of exposure tomorrow. The accounting exercise, though, is fraught. How do you add up all the money not wasted or stolen?

Another way of accounting is to consider the public resources governments spend to promote themselves and sanitize information, versus the costs of empowering citizens through freedom of information. At the federal level, at least, some numbers are available.

Administering the Access to Information Act cost Ottawa a net $89 million in 2020-21. Most of that is salaries, benefits, overtime and IT-related costs. The system is riddled with inefficiencies, but leave that aside for now.

Ottawa spent $129 million on advertising in 2020-21. Much of that is COVID-related – the number was a more typical $50 million for 2019-20.

Public-opinion research in 2020-21 cost $15 million, with no significant COVID effect. (The annual average for the last five years was $13 million.) Polling helps government shape and fine-tune its public messaging, and is mostly outsourced.

Then there is an army of media-relations staff, in ministers’ offices, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations. As veteran Ottawa reporters well know, the numbers have swollen tremendously over the last two decades, joined by speech-writers, photographers, social-media specialists and others.

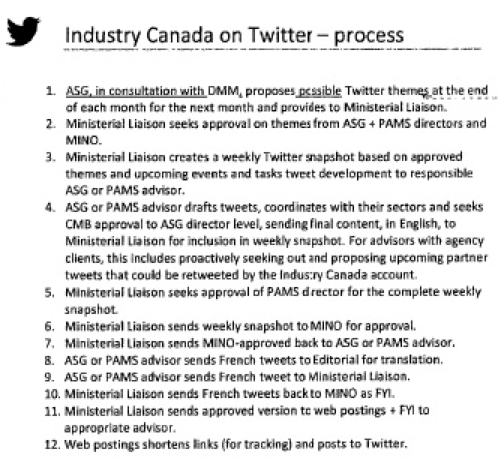

Crafting individual tweets seems to require large crews of drafters, vetters and editors. More than 30 people were involved in creating a single, botched tweet from then-environment minister Catherine McKenna in 2017. Industry Canada instituted a 12-step process for approving each departmental tweet, involving dozens of people.

The cost of all these media- and public-relations workers is not easily calculated. The Canadian Armed Forces employs 183 public-affairs officers in the regular force, typically captains who earn $70,000 a year, costing at least $13 million. My colleague David Pugliese, an outstanding defence reporter, estimates the total annual cost at about $32 million when taking into account civilians, reservists and others in public affairs.

Advertising ($129 million), polling ($15 million) and just one department (National Defence – $32 million) together cost $176 million. Even if we discount COVID-related advertising costs, the bill at $97 million is still higher than the $89 million for access to information. And we haven’t even begun to tote up the salaries of hundreds of workers who do media relations, public affairs, speeches and tweets in ministers’ offices and departments.

You never hear officials like Lisa Beare rail against the high cost of government advertising, or polling or the small army of flacks on the public payroll. After all, dollars that help governments manipulate information provide good value. But accommodating citizens’ rights under freedom of information? Those costs are wildly excessive.