Sweden: An FOI Eden?

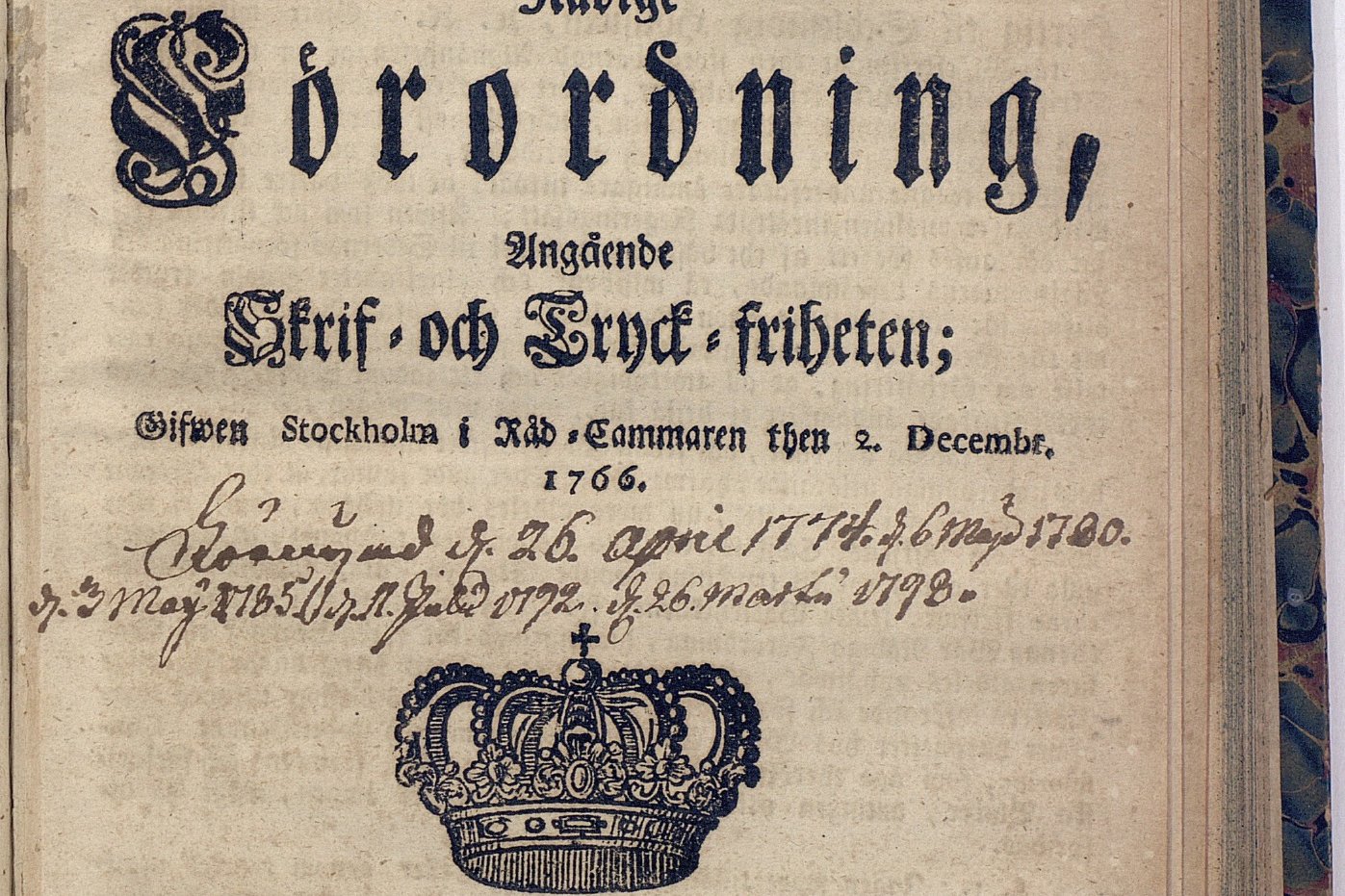

Sweden is frequently touted as a paragon of freedom of information. After all, Sweden claims to have passed the world’s first FOI law, on Dec. 2, 1766.

The country’s FOI credentials were on full display in 2016, when Sweden celebrated the 250th anniversary of the law. (Finland joined the festivities, given that it was part of Sweden at the time.) In Ottawa, Swedish ambassador Per Sjogren testified to a House of Commons committee reviewing Canada’s Access to Information Act, offering his FOI perspectives. The embassy also set up a display at Library and Archives Canada, chronicling the twists and turns of Sweden’s FOI experience since 1766, with its many rocky moments.

At the time, I spoke with Sjogren and his staff to learn first-hand how FOI worked in modern Sweden, with special reference to journalism. The picture they painted was rosy. FOI is written into the constitution. Swedish bureaucrats are steeped in FOI culture, trained to nimbly respond to requests for documents. Schools teach young students about their information rights. Citizens expect government to produce documents on demand, including cabinet records. Fees are negligible. Sjogren spoke of his personal experience: whenever a journalist requested documents, he had to drop everything and respond with alacrity.

It all sounded too good to be true. So I went to Stockholm to talk to journalists about their direct, day-to-day experience. Sure enough, there was trouble in paradise. Senior producers and reporters at the public broadcaster cited a raft of problems.

Under Swedish law, internal communications of a police force are protected, while external communications with other domestic forces are subject to FOI. But the country restructured policing, amalgamating a dozen or more local forces, so communications became internal and unavailable.

Like many modern states, Sweden has outsourced some health and education services to private entities. Journalists found that wherever this occurred, they lost FOI access to documents previously available when the state supplied services directly.

Sweden’s decision to join the European Union in 1995 created new barriers to its FOI regime, which protects economic interests and state-to-state contacts. Growing economic integration and broader diplomatic relations with EU countries has gradually curtailed access to more documents.

Cabinet records are covered by FOI, but only those registered by government as “official,” which leaves some material inaccessible. Draft versions of documents are generally not available unless no final version was created. Bureaucrats are often unwilling or unable to provide searchable databases.

It’s hardly surprising that Swedish journalists find fault with some of the law’s shortcomings, just as we do in Canada with our law. What is surprising is that Swedish journalists use it almost daily, because it’s so easy. No form or fee is required to request a document, and most requests are made by telephone or email without even invoking the law – the constitutional right to access is understood and accepted by both sides.

Swedish courts have ruled that public servants must respond to requests immediately, that is, the same day or up to a week if many documents are involved. Sjogren’s claim that public servants must put everything else aside and deliver requested documents promptly was confirmed by journalists in Stockholm. One of them told me: “We are very bad at covering business because it’s much easier getting government information.” She added that journalists often get faster service than members of the public.

The day I wrote this blog, I received a final response from VIA Rail to an access-to-information request that I had submitted to them on March 17, 2017. That is, it took almost five years to receive the document. Long delays are built into Canada’s faltering FOI system, making it less and less relevant to journalism.

Sweden’s FOI regime is clearly not perfect, and indeed has some of the same problems faced by our own system. But if there’s one thing we can learn from the Swedes, it’s timeliness. There, public servants scramble to get out a response in a day or two. In Canada, timelines are measured in months and years.

March 7, 2022