Spies, lies and the convoy

The twilight world of espionage inspires liars, both inside our spy agencies and out.

On the inside, deceit is a tool of the trade. For spymasters, it’s also a handy cover for incompetence.

On the outside, storytellers such as journalists often lose their bearings. They accept the claims of their unidentified sources with little challenge or fact-checking, all in the pursuit of a ripping spy yarn. Never mind that the stories are baloney.

For both groups, the ground is safe because of secrecy. Security and intelligence, after all, is secret work. Governments must hide their efforts to keep citizens safe, lest the enemy get an advantage. And so a cloak is drawn across these agencies, with an assuring “just trust us.” In telling stories, there’s almost no prospect of contradiction because information is kept carefully under wraps. It’s a wonderfully blank canvas.

In 1942, the German intelligence agency landed a spy by U-boat on Canada’s East Coast. He was caught within hours, and turned into a double agent. He was forced to send concocted messages back to Germany by short-wave radio in a deception campaign. This was Canada’s first major foray into international espionage.

After the war, many wanted to tell the story. Journalists, military men, RCMP and others competed for the juiciest, most dramatic accounts. Newspapers, magazines and books each carried gripping versions. Many were misleading. Some were bare-faced lies. But it wasn’t possible to reconcile competing versions, because the original 3,000-page RCMP file was locked away forever.

That is, until the Access to Information Act came into force in 1983. Through the Act, I accessed a lightly redacted copy of that RCMP file. I wrote a book, Cargo of Lies, that exposed much of the incompetence in handling the double-agent. It also showed that various public versions of the spy story were bunkum.

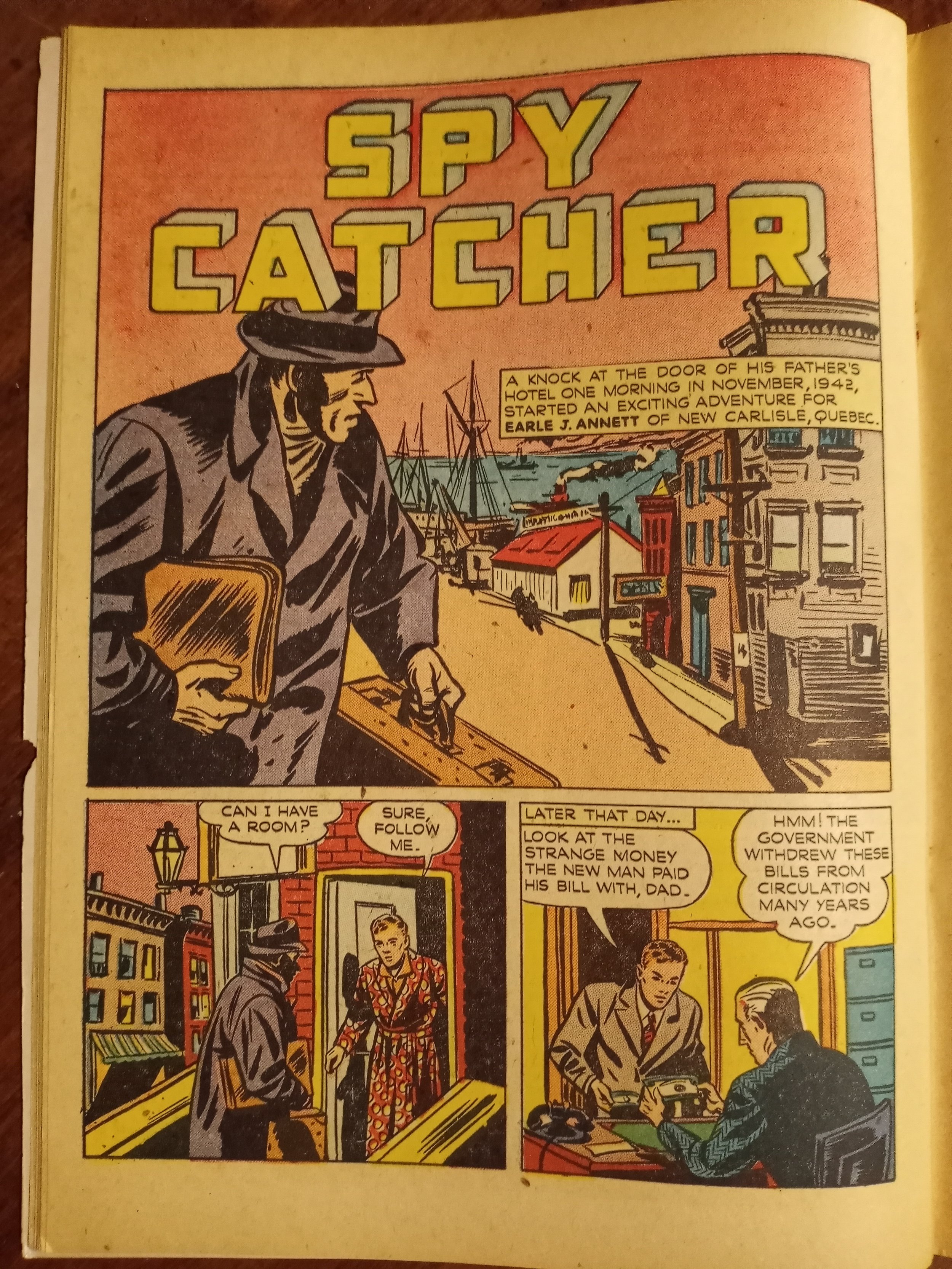

I thought about this spy case when I recently acquired a musty 1946 comic book that told the double-agent story in a few panels (see above), and a 2019 graphic novel in French that elaborated on it (see below). Both were fun to read, inspired by the wartime events but embellishing them significantly. They were a reminder that we love to tell stories, and facts are sometimes an annoying impediment.

We also have transparency legislation. The Access to Information Act has many faults, including a loophole that protects too much security-and-intelligence information. But when it works, it can cut to the truth and expose incompetence and lies.

I also thought about the double-agent case during recent news coverage of the Public Order Emergency Commission, which is looking into the so-called convoy protests that paralyzed Ottawa for weeks. The commission has compelled release of reams of documents, most of which would never be available under the Access to Information Act. The material is a rare glimpse inside police intelligence collection and analysis. What we’re learning is disconcerting, raising disturbing questions of competence and bias. The material also begs the question: have internal problems flourished under a cloak of secrecy?

The commission’s work should make us ever more sceptical of the blanket protection we afford our security and intelligence agencies. And it should increase the pressure to close those secrecy loopholes, for our own protection.

Oct. 29, 2022