Sherman, set the WayBack Machine …

Most news has a best-before date. That’s why it’s called news. As Mick Jagger of the British think-tank The Rolling Stones observed in 1967: “Who wants yesterday’s papers? Nobody in the world.”

Canada’s politicians know that stale information is harmless. So in the early 1980s, they inserted into the Access to Information Act several clauses to ensure key government records will be mouldy before citizens ever get a chance to read them. These clauses all invoke a 20-year rule, with no rationale given for the length of the waiting period.

Law-enforcement and security records can be safely locked up for at least two decades under Section 16(1)(a). The same for any advice or recommendations provided to government, according to Section 21(1). In each case, the Act says departments “may refuse to disclose” the records for 20 years, but almost all seize the opportunity, making it a de facto “shall refuse to disclose.”

The Act also safeguards personal information under Section 19(1), with a special twist: the dead carry their privacy rights to their grave for a further 20 years. (The 20-year clause is actually in the Privacy Act but applies to the Access to Information Act.) In contrast, the dead in America have few privacy rights under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act.

Finally, cabinet records in Canada are safely buried for 20 years. Over that period, they’re shielded entirely from the Act – the legislation simply does not apply to them. Only after two decades do they come under the umbrella of the legislation. Even then, there are many legal reasons to further withhold them, such as security risks or protecting federal-provincial relations.

Various studies and reports have urged governments to roll back the 20-year barriers, to no avail. For now, journalists must live with them. Here’s one approach.

Set the WayBack Machine to the year 2002. What was going on two decades ago? If your memory fails like mine, consult online tools such as this Wikipedia page listing news events and deaths of prominent people in Canada. I’d forgotten that the novelist Timothy Findley died that year, or that Jean Chretien had fired his finance minister, Paul Martin, both events occurring in June.

Now you’re ready to ask for documents under the Access to Information Act. Did the RCMP Security Service keep a file on Findley? Findley was an actor who visited the Soviet Union in the 1950s. Were our spies keeping tabs on him in Moscow? What did Chretien tell his cabinet after dumping his rival, Paul Martin? How was it received?

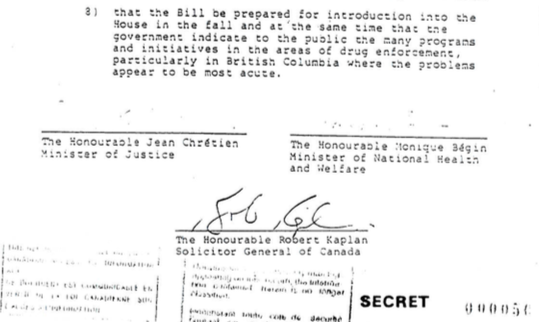

Ottawa journalist Jim Bronskill, a friend and clever colleague, has worked these historical veins with wily tenacity. He asked for security files on Tommy Douglas (died 1986), for example, and on Pierre Trudeau (died 2000), submitting his requests months before the actual 20-year anniversary to account for slow ATIA processing. His Douglas and Trudeau stories each exposed wacky practices, and won headlines everywhere. Many Quebec journalists accessed key cabinet records 20 years after the 1970 October Crisis, peering into decision-making of that grim period. I’ve obtained many older cabinet records that still generated news, such as a 1981 initiative by then-Justice Minister Jean Chretien to radically reform marijuana laws. Cabinet killed his proposal.

Here’s a prediction: over the next year, we’ll see news stories about Canada’s response to the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, based on cabinet minutes now more than 20 years old. So much happened – the creation of CATSA, for example, or the military deployment to Afghanistan – that those intense discussions behind closed doors will likely make news today, despite politicians’ efforts to make it all seem stale.

Feb. 9, 2022